Plastic Parts - 3D Printing and CNC Machining

Not so long ago, having prototypes or a few production parts machined was a more costly and time-consuming process.

You mailed a paper drawing to your favorite machine shop, had a short chat with the owner or shop foreman to discuss the due date and price, and waited.

If you were in a hurry, maybe you paid for the overtime to get the parts done sooner, but prototyping was still an exercise in patience. You could get real parts but at the cost of valuable production time and money.

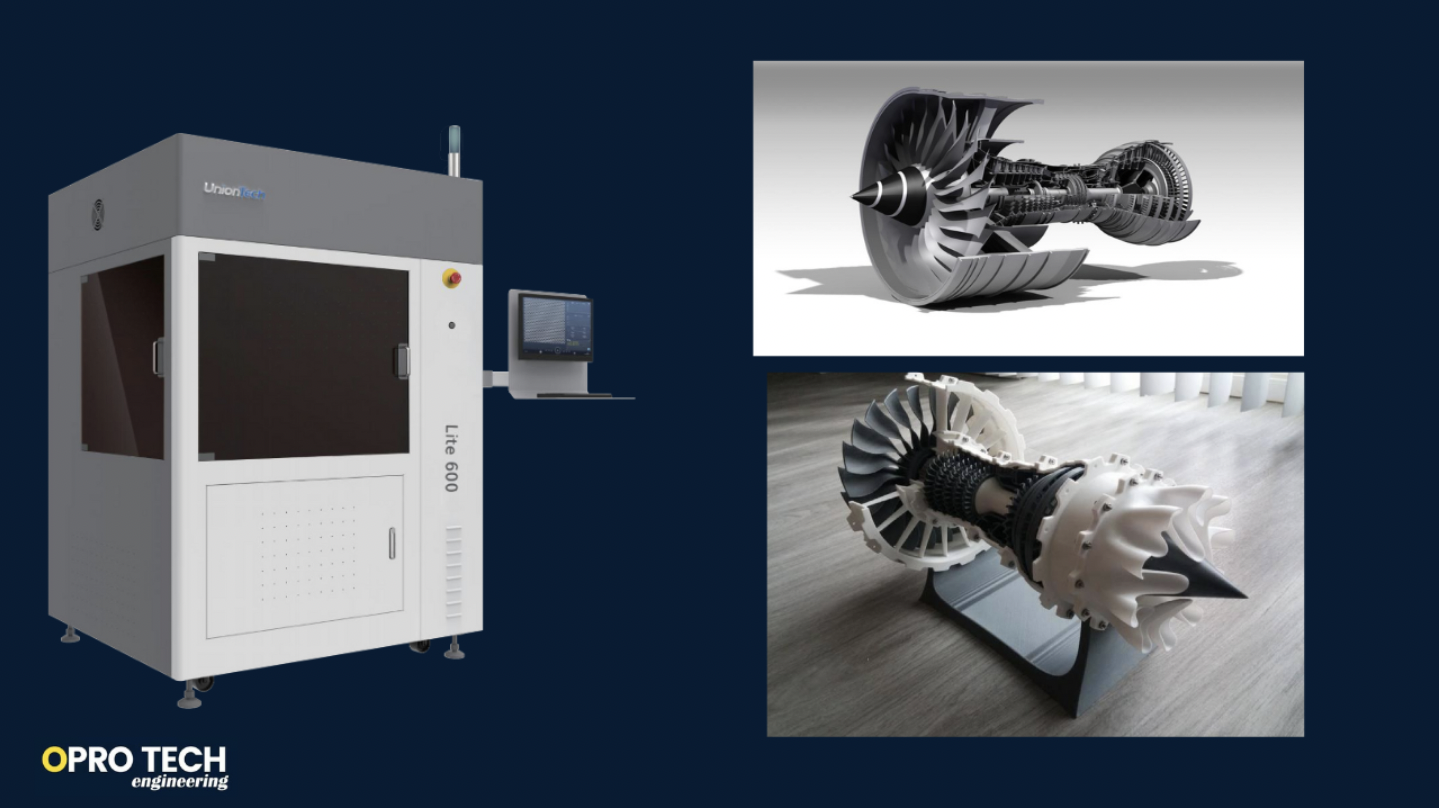

Then came the service bureaus with their 3D printers.

Plastic prototypes could now be ordered quickly and far more affordably than hiring a local shop to set up a machine.

The only problem was the material—early-generation stereolithography (SL) systems were limited to one or two types of liquid resin photopolymers, good only for “show and tell,” or as patterns for casting and molding.

Additive manufacturing was in its infancy. Soon other methods with their confusing acronyms became available.

One of these is selective laser sintering (SLS), which uses a powder bed of

nylon-based material rather than liquid resin. This eliminated the need for support structures during the build process as with SL, thus reducing post-processing and saving time and money.

Stereolithography wasn’t sitting on its laurels during this time. SLA parts today are made from a range of resins that mimic some of the properties of engineering plastics.

These are available in different colors and strengths, making them suitable for more than dog-and-pony shows.

Machining has evolved over the years as well. For example, Opro-tech's CNC machining service can deliver machined parts, in both plastic and metal, in less time than it takes to get a quote from other, more traditional machine shops.

Send us a CAD file, the material, and part quantity, and tell us when you need the parts. Chances are you can have parts within a very short period and at a cost that is comparable to 3D printing, if not cheaper for certain geometries.

However, the problem today is one of choice.

How does a product designer or engineer know which process is best suited for his or her part design? Since machining has been around at least a century longer than additive manufacturing, let’s start there.

Material Selection

For the most part, plastic is very easy to cut.

Granted, glass-filled materials are somewhat hard on the end mills, and acrylics can chip. Teflon is slipperier than a politician. But for the most part machining plastic is as easy as it comes.

Opro-tech Ltd can machine more than three dozen types of engineering-grade thermoplastics.

Acrylic, acetal, ABS, nylon, PC, PP, PEI, and PEEK—these and a host of other plastics cover the needs of nearly any part design imaginable.

Final machined plastic parts can be used for form and fit testing, and even as functional parts in many cases.

On the 3D printing side of plastics, material options are more limited. SLA parts are built from photopolymer resins that mimic some properties of plastic like ABS, PC, and PP.

They work well for prototyping form and fit, but for functional parts, machined plastic is the route to travel if the design allows.

Now the story is a bit different with SLS, which uses actual thermoplastic nylons to build parts. This process tends to bring added durability and stiffness to 3D-printed parts, but color options are black and white, and surface finishes aren’t nearly as nice as for machine parts.

Geometry

Where the machining process sometimes comes up short is part geometry. Opro-tech Ltd uses 3-and 5-axis indexed CNC machining centers. An engine bracket, a camera body, the baseplate for a thermostat or even the thermostat housing itself—these are good candidates for machining.

Sharp internal corners on vertical walls are challenging, as are undercuts and pockets deeper than a couple of inches, but almost everything else is fair game.

Cylindrical plastic parts—a drive shaft for a snowmobile, or the next greatest trailer ball hitch—can still be milled (or 3D printed) until then.

And then there are some part designs that machining can’t touch. That’s when the additive steps up to the plate. It would be impossible, for example, to machine a whiffle ball, whereas SLA and SLS can build that with ease.

Machining the internal cooling channels in a heat exchanger would likewise be a challenge, but is possible in additive manufacturing.

Other parts are a toss-up. A class ring can be machined or printed, but milling away the material inside the ring would be both wasteful and time-consuming. The same holds with a picture frame or a set of napkin holders. Because it can print just the material needed, additive wins.

Another large consideration to factor in with geometry is whether or not the part will eventually move into a manufacturing process with the ability to produce larger quantities, e.g., injection molding.

A machined part typically has an easier path to molding than an additive part for two reasons: The material used in machining can more easily be duplicated in the molding process and printed parts with highly complicated geometries will most likely have to be modified to be molded effectively.

Tolerances and Surface Finish

Aside from material choices, there are other important differences between plastic 3D printing and machining processes. In terms of accuracy and surface finish, machining tends to be more accurate and has better long-term dimensional stability than SLA parts, with surface finishes being approximately equal between the two processes.

SLS parts have rougher finishes than SLA or machined parts, and are more stable than SLA parts and approximately as dimensionally stable as machined nylon parts.

Prototyping with Injection Molding

The wild card in the additive versus machining plastic conversation is quick-turn injection molding. Even though injection molding at Opro-Tech Ltd is often used for low-volume production, most customers also use the service for manufacturing small quantities of prototypes and production parts with a similar turnaround as 3D printing and machining.

If this is the case, different design considerations in areas like the aforementioned material selection, geometry, and tolerances come into play.